Quod Nomen Mihi Est?:

Excerpts from a Conversation With Satan

|

|

Paul Pfeiffer

I was 10 years old the first time I was possessed by the devil.

It happened in the small city of Dumaguete on the island of Negros

in the Philippines, where I was attending sixth grade at one of

the oldest American missionary schools in Asia. One night I was

jolted from my sleep in the wee hours of the morning by a terrifying

feeling. I woke to find my room and my body completely out of proportion.

My head and hands felt too big for my body. My heart was racing.

And as I looked around the room my sense of space was becoming monstrous

and strange: my vision felt decentered, like I was floating outside

of myself; everything around me was small and far away, like I was

looking through the wrong end of a telescope. Or maybe it was that

the room was looking at me. It was full of a presence that penetrated

me with a gaze that seemed to come from every direction at once.

I jumped out of bed, ran out of the house, and still barefoot and

in my shorts, began walking instinctively in the direction of sunrise.

I didn’t stop or turn around until the sky began to glow a

dull blue and the birds announced the coming dawn.

At the time of this encounter, if anyone had asked the question

“What scares you?”, I would have answered with a series

of movie titles: Jaws, Helter Skelter, The Amityville

Horror, The Exorcist. The last two of these, The Amityville

Horror and The Exorcist, both entail scenarios of demonic

possession in enclosed domestic spaces, and both scared me so much

that I never dared to watch them. But that didn’t stop me from

thinking about them with a kind of morbid fascination, to the point

that I practically reinvented the scenes over in my head. So when

I woke up that night in the Philippines, I recognized my altered

state of consciousness as a sign that the devil had entered me and

I was possessed. After that incident I became afraid of my room,

and of sleeping in the dark, quiet heat of the tropical night. For

what seemed like a long time afterward I dreaded the moment when

all the lights in the house would go off and I would be left alone,

lying awake in my room with Satan waiting for me to drift off to

sleep.

There is a book that brings me back to the scene of childhood terror:

the novel Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. Set in the

late 1800s, at the height of the industrial revolution, Heart of

Darkness follows the trail of Marlow, a young seaman, up the Congo

River where he has been sent by a mining interest called The Company,

to survey the expanding imperial domain of King Leopold of Belgium.

More specifically, he has been sent to look for the enigmatic Kurtz,

a Company agent who has cut contact with the home office, and whose

activities in the furthest reaches of the African jungle are now

a matter of suspicion and doubt. The novel could be read as a fictionalized

travelogue: a geographic and historical account of the events and

landscape during the heyday of European colonial expansion. Yet

as Marlow goes deeper and deeper into the African continent, his

journey becomes as much psychological as geographic. He reaches

his final destination at the end of the book to discover he has

come full circle, facing not a dark secret about the jungle but

a dark truth about himself and the values of his society.

The plot is surely familiar to all by now, if not through Conrad’s

book, then through the various Hollywood remakes that have come

since: from Orson Welles’ adaptation for radio, through Francis

Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, to his wife Eleanore’s

subsequent expose on the making of her husband’s epic, to Nicolas

Roeg’s telenovela starring John Malkovitch as Kurtz and Iman

as his jungle bride. More broadly speaking, Heart of Darkness

belongs to an age-old narrative structure that is the basis of every

journey into the unknown, a pattern that extends from Oedipus

to Star Wars, from Medusa and the Sphinx to Aliens,

from Homer’s Odyssey to Pigafetta’s journals, Nanook

of the North, South Pacific, Lost Horizons, Jungle

Fever. Many have sought to understand the endurance of this

pattern. There is much to support the theory that the hero’s

journey is the very spark and engine of the narrative drive itself.

Nor is the jungle setting of Heart of Darkness particularly

new. The homes and bodies of black people, of women, and the poor

have always been the preferred site for the hero’s transgressions.

Yet two things distinguish Conrad’s version of the plot, the

first being that it takes place just as the foundations are being

laid for the economic order we live in today. Contemporaneous with

the Philippine American war, Marlow’s journey up the Congo

— and by extension, up all the Congos of the world — is

the precise journey into nature that makes global capitalism possible.

The second thing that distinguishes Heart of Darkness is

its psychological depth. Written at about the same time as Sigmund

Freud’s early lectures on psychoanalysis, Heart of Darkness

is full of descriptive clues and literary symptoms that provide

a window into the perceptions and phantasms of the Colonial imagination.

The novel stands as a rare case study of the Western psyche at the

dawn of the modern era. Marlow himself narrates: “It would

be interesting for science to watch the mental changes of individuals,

on the spot. I felt I was becoming scientifically interesting.”

And what characterizes this psychological profile? As we follow

Marlow upriver, we find his perception of the jungle becoming increasingly

paranoid. He says, “I had... judged the jungle of both banks

quite impenetrable — and yet eyes were in it, eyes that had

seen us.” Throughout the story the feeling of eyes watching

from the trees grows stronger, until it seems it is not just animals

or people watching but something much bigger, maybe the jungle itself.

“The inner truth is hidden — luckily, luckily. But I felt

it all the same; I felt often its mysterious stillness watching

me at my monkey tricks...”

Towards the end of the journey Marlow’s boat is enveloped by

a dense white fog. As it descends, the crew is filled with fear

because suddenly they are robbed of their power of sight —

that primary, if paranoid, sense perception that has kept them centered

on their tenuous course up river, and has protected them from running

aground on the shallow banks. More disturbingly, without the benefit

of a panoramic view it becomes virtually impossible to judge depth

and distance with any accuracy, much less to maintain a safe distance

from the threatening presence in the trees. In this moment of sensory

overload the jungle rushes in, becomes suffocating and tactile,

seeps into the very pores of their skin. Marlow recounts, “Our

eyes were of no more use to us than if we had been buried miles

deep in a heap of cotton wool. And it felt like it too — choking,

warm, stifling.”

This is an identity crisis in the deepest sense: a face to face

encounter with an other, where the boundary between subject and

object, self and other, narrator and story, Marlow and the jungle

seems to blur and disappear. It is a moment rich with visual resonance:

imagine a mode of perception so paranoid that visual reality seems

to fall apart, and ceases to make sense. In such moments, distinctions

between inside and outside, nationality, religion and language lose

their power to explain. For an artist this is the moment of truth.

In a scene from the 1972 blaxploitation thriller Across 110th

Street, a Mafia don stands at the window of his Central Part

South apartment, looks out across the trees, and says to his son-in-law,

“What do you see?” The heir apparent answers, “Central

Park.” To which the don replies, “Central Park, si. But

there is also no man’s land that separates us from the blacks

in Harlem.” In October 1998, as I was preparing to mount an

exhibit at the newly opened gallery The Project on West 126th Street,

I thought about this scene, and about what it would mean to have

denizens of the downtown art world going uptown in search of new

art. Of course, New York’s bohemians and investors have always

looked to the more exotic parts of town for novel thrills and new

ideas. At this moment it is already too late to buy up property

above the park. Disney is opening a mall right down the street.

Still, when people started asking if it would be safe to go up and

see the show, I knew that they were not referring to the threat

of police harassment.

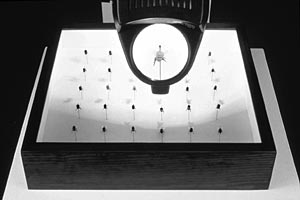

The central piece in the exhibit was conceived as an extension of

the downtown patron’s journey uptown into the Heart of Harlem.

You would come out of the subway on 125th, walk one block north

and two blocks west until you arrived at the gallery. Once inside,

you would go downstairs into the basement and through a dark hallway

to find a wood and glass display case, a replica made from a 1911

photograph in the archives of the American Museum of Natural History.

Inside the case was a little diorama of a jungle scene, and in the

middle of the jungle was a little white tent. The contextual details

of the scene were left purposely minimal. The historical setting

was specific. It could have been any jungle in the world, but it

definitely had to be somewhere in the tropics. And the tent would

indicate that wherever this was, there was somebody there who was

not at home in the terrain.

Moving into a second room, you would then find a large, floor-to-ceiling

movie screen, onto which was projected a life-sized image of a tent

against a leafy background. If you were to move back and forth between

the room with the projection screen and the room with the jungle

diorama, you would realize that you were looking at a live-feed

video signal coming from inside the glass case. This was made possible

via a tiny surveillance camera hidden in the trees, and pointed

at the tent. If you looked hard enough you could even see the peering

eyes of other viewers looking at the diorama, caught on camera and

projected as giants among the trees. Going upstairs again, you would

then find an arrangement of peep-holes set into the wall in a dark

corner of the main gallery space. Looking into the peep holes you

would see another live-feed image of the room downstairs with the

diorama you had just left. If there were people downstairs, you

could observe a fly’s eye view of the viewers peering at the

little tent in the little jungle of the diorama.

The title of the piece is Perspective Study (After Jeremy Bentham).

Jeremy Bentham was the architect of the Panopticon, the pioneering

18th century prison design that would become the template for the

modern penitentiary, among other things. The central principal of

the Panopticon is total visual access to the inmate’s every

move. The guard is positioned at the center of a multileveled rotunda;

the prisoners’ cells are spaced evenly along the inside perimeter.

The front of each cell is made of metal bars so that the captive

is in plain view at all times. The inmates cannot see each other,

only the guard tower. The observer in the tower at the center sees

all. As for the Perspective Study that makes up the rest of the

title, it is a reference to a famous etching by Albrecht Dürer,

the 16th Century artist and proto-naturalist. The etching shows

the artist in his studio surveying the world (a female model) through

the newly invented technology of the Cartesian grid. In the Perspective

Study (After Jeremy Bentham) in Harlem, the viewer is enveloped

and positioned within a web of shifting perspectival lines —

a network of ocular relationships, of seeing and being seen. There

is no singular “meaning” to the work. It merely functions

as a three dimensional schematic diagram for your consideration.

You may note, however, that there is an implied obverse relationship

between the Panopticon and Marlow’s jungle. The suggestion

is this: that the man who sees and controls all must also be the

most paranoid man alive.

The mechanics of

perception and the formation of identity have always been intimate

bedfellows. At the dawn of Western architecture, the ordering of

space through strict laws of proportion was not just about making

a shapely building; it was a projection of an imagined accord between

individual bodies, social relations, and the natural universe. In

the Renaissance, as many studies have shown, the discovery of linear

one-point perspective and Cartesian space was pivotal in laying

the foundations of modern science. In 1936, Walter Benjamin made

the link explicit in the context of Marx’s theory of class

struggle when he wrote, “During long periods of history, the

mode of human sense perception changes with humanity’s entire

mode of existence.”

The matter of human sense perception becomes a question of faith

in the 1973 horror classic The Exorcist. In the movie, a

modern family unit in the nation’s capitol struggles to come

to terms with a rather severe identity crisis on the part of their

daughter, Regan. Regan develops a series of bizarre, and baffling

symptoms: she flies off her bed as though propelled by some unseen

force; she speaks in a voice that is not her own; she pees on the

rug in the middle of a cocktail party and announces to the guests,

“You’re all going to die up there;” she stabs her

face and genitals with a crucifix, shouting to anyone who will listen,

“Let Jesus fuck you.” Her head spins 360æ on her neck

in defiance of the fundamental laws of human anatomy. After all

else fails to cure the child, a priest is brought in, Father Karras,

who attempts to discover the identity of the demon by engaging him

in conversation. Father Karras asks, “Quod nomen mihi est?”

Who are you? To which the devil replies, “La plume de ma tante,”

the tail feathers of my aunt. Sheer nonsense.

So who is the devil? If we follow Regan and her family closely through

the movie some interesting clues emerge. Before the demon even makes

his appearance, we find that Regan has already been possessed on

two different counts: first by Hollywood, and second by Medicine.

In an early scene of the movie, Regan’s mother, played by Ellen

Burstyn, goes to tuck her daughter into bed and finds her asleep

with the lights on. Sticking out from under her pillow is a Hollywood

fan magazine. The mother picks it up, at which point we discover

that she is, in fact, a famous movie actress, because there before

us is her face is on the cover of the magazine. Along side her we

also find Regan’s smiling face, suggesting that by default

she has become a part of the film industry, her life permeated by

her mother’s on-screen personality and career.

Later on in the movie as Regan starts to become “sick,”

she is brought to the hospital where she is subjected to a series

of grueling and invasive medical tests. She is strapped to a metal

bed under fluorescent lights, she is surveilled via closed circuit

TV, she is injected with dyes, brain scanned and x-rayed, and tapped

for spinal fluids. The hospital scenes are in fact some of the most

graphic in the movie. In one particularly terrifying scene, Regan

is strapped to an operating table, and an intravenous needle is

inserted into her neck, sending blood spurting out in spasms. The

needle is then taped down and used to pass a long plastic tube through

her neck and deep into her body.

What are we to make of such images? Are we to see a link between

the media, the medical establishment and the forces of evil? Does

it even make sense to think about technology in religious terms?

From the earliest days of this century, new technologies —

from the movie camera to the microscope — have been the source

of deep feelings of ambivalence, promising transcendence to a new

level of human consciousness, while at the same time representing

a Pandora’s box leading to self-destruction. But the human

propensity for both good and evil is nothing new. Questions of ethics

predate the advent of genetic engineering, just as the idea of community

predates the interactive CD-ROM and the internet. If anything, the

invention of powerful new technologies merely increases the stakes,

multiplies the costs, and heightens the impact of established values

and morals on our daily lives. As Donna Haraway puts it, “It

means there has been a deepening of how we turn ourselves, and other

organisms, into instruments for our own end.” Like a guilty

wish or an unconscious desire, technology is already deep inside

you. The more you deny and repress its existence, the more it grows,

and grows against you, until it returns as an alien being from another

dimension. This is what for me remains compelling about the movie

The Exorcist: the vision of an evil doubly terrifying because

there is no possibility of shutting it out or running away; no escape

because it is inside you; without recourse, even, to any distinction

between you and it.

The diaspora is not about us, it’s about Michael Jordan. To

see him soar through the air, a sparkling, shiny creature traveling

at the speed of light, landing in every first, second, and third

world city all at once, is to understand you play a minor role in

a very big game. He has visited more of your extended family than

you could ever dream to. His reach defines the meaning of community

in the television age. In the Philippines, voter turnout for nationwide

local elections in 1996 reached a record low during the airing of

game six of the NBA playoffs (the Bulls won). When Jordan announced

his retirement in January 1999, his life and times were the top

story in the daily news of your home town.

It is no coincidence that black is the color of his skin, the color

that fills the TV screen in your living room. Black has always been

the color to express the depths and furthest frontier of the knowable

universe. Like the scientist-turned-insect in the sci-fi classic

The Fly, Jordan is an experiment in human evolution: an exceptional

talent re-packaged and distributed by Turner Sports and David Stern;

grafted with 16M parts Nike, 5M parts Bijan Cologne, 5M parts Gatorade,

4M parts MCI WorldCom, and 2M parts Rayovac Battery.

Editha Bensi, a working class home maker and mother of five from

the Central Visayan island of Cebu, is another face of the diaspora.

A vial of her blood appeared along side three others on the cover

of the New York Times Magazine on April 26, 1998. Her family’s

blood is a genetic gold mine: for generations the mutant gene considered

to be the cause of cleft lip and palate disease has been running

through their veins. Editha Bensi’s DNA is now part of the

Human Genome Diversity Project, a detailed road map of disease genes

that promises to one day provide an “operating schematic for

mankind — a detailed picture of who we are and how we work.”

For her services she is given a plastic washtub, a beach ball and

a thermos, a fast-food lunch, and candy and cookies for the children.

On the agreement she signs with the project, the stated reason why

she is not paid in cash is that “...money is a means of coercion,

and compliance cannot be truly informed and voluntary if it is purchased.”

When the doctors come to take blood samples from Editha Bensi’s

children, they struggle to free themselves from doctors’ grip

and run away. Mrs. Bensi explains that they are fighters, that they

have had to be because they are different. And when Operation Smile

arrives with the opportunity for corrective facial surgery, Editha

Bensi flatly refuses. The doctors and her husband attempt to persuade

her, and she snaps, “You said it didn’t matter how I look.”

So why did she agree to give blood to the geneticists? For the good

of medical science? For the benefit of future generations? When

asked, her answer is clear and simple, “Because they wanted

it,” she says. “Because they asked.” How often had

she and her family been regarded as the objects of fear, ridicule,

and suspicion. Had she ever been approached before as the bearer

of knowledge, the one holding the key to understanding the world?

On February 4, 1999, about a year after his arrival in New York

City from Guinea, Africa, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, Amadou Diallo,

an unarmed twenty-two year old, was murdered in the entryway to

his apartment in the Bronx by four plain clothes policemen. They

said it was a mistake, that they were suffering from Marlow’s

jungle disease: they panicked in the face of an illusory threat

they thought to be real. A child of the diaspora, Amadou Diallo

was, after all, W.W.B. when they shot him — Walking While Black.

There is no mistaking the message written in a shower of forty-one

bullets from four semi-automatic handguns in nine seconds. The letter

of the law has always been written in black ink on white paper.

And the message is this: In the richest city of the richest nation

in the world, we will do anything and stop at nothing to protect

our interests and the lifestyle to which we have become accustomed.

On 126th St. in Harlem, just down the street from The Project, there

is an Episcopal church which flies the African liberation flag above

its steps. The meaning is clear if you turn your head to the police

precinct across the street. The new diaspora is not about crossing

national borders, biracial babies, or dual citizenship. There is

no such thing as being in between two cultures, half and half, or

the best of both worlds. It is a battle between good and evil, a

question of morality, a matter of faith. A dense white fog is descending,

your sense of space and time are becoming monstrous and strange.

The devil lives behind your eyes, his name is branded on your flesh,

he is built into the structure of your DNA. He is knocking on your

door. It doesn’t matter if you let him in. He is already traveling

in the blood through your veins.

|